Intro

The Camorra, unlike the Sicilian Mafia, was noted for its use of written rules and codes of conduct, documented in use at least since the 1890s. This use of written statues presumably derived from the practices of clandestine political secret societies that flourished in 19th Century Southern Italy and influenced the rituals and organizational structures of the Camorra (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014; Gratteri & Nicaso, Storia segreta della 'ndrangheta: una lunga e oscura vicenda di sangue e potere (1860-2018), 2018). Even today, the modern ‘ndrangheta, which derives from the old Camorra of the 19th Century, has continued to make use of written codes, which have been discovered both in Calabria and abroad[i]. These rules provide us with a glimpse into the traditions of the Camorra and its evolution from a phenomenon of the prisons of Southern Italy to a phenomenon dispersed across communities outside of prison. Critically, the recovery of similar written codes in the early 20th century in the United States help us to identify the infamous networks of “black hand” extortionists and counterfeiters operating during that period as including iterations of a shared, trans-Atlantic Camorra tradition that stretched from Calabria to North America.

The Sicilian Mafia

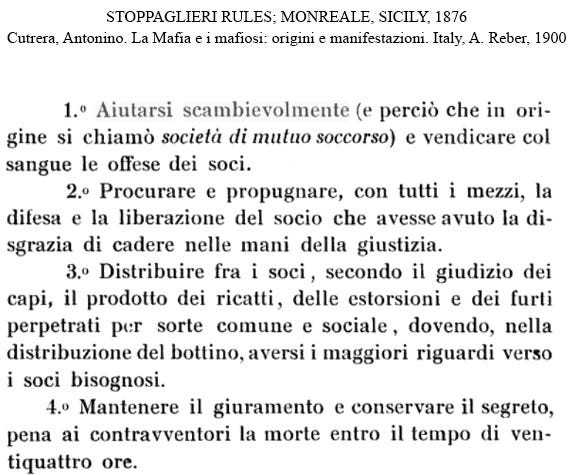

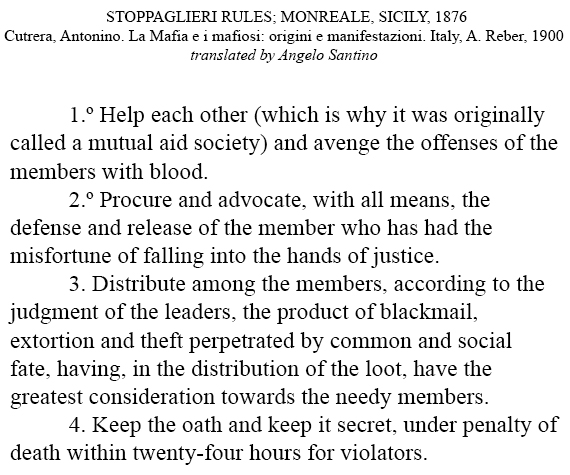

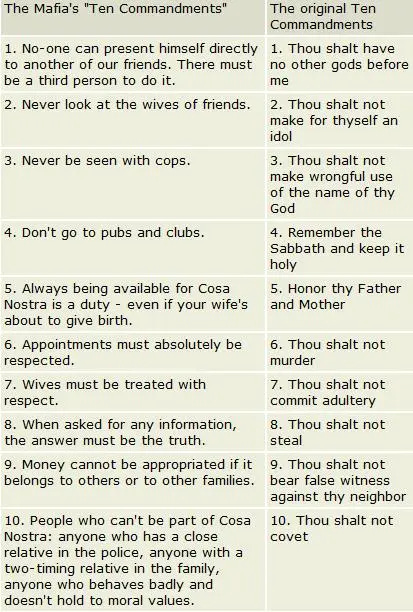

The use of written documents by Camorra affiliates stands in stark contrast to the Sicilian Mafia[ii], where rules and codes of conduct are traditionally passed down orally. The first example we have of a set of Mafia rules was recorded in Monreale, in the Sicilian province of Palermo, where in the 1870s investigators learned of the rules of a Mafia “sect” founded around 1871, known locally as Stuppagghieri (“the barrel stoppers”) (Cutrera, 1900).

In 1885, affiliates of a Mafia organization called Fratellanza (“Brotherhood” ) or Mano Fraterna (“Fraternal Hand”) were arrested and tried in Favara, Agrigento province, Sicily. Notably, investigators recovered written statutes from the leaders of the group, which was organized along the lines of a mutual aid society (Fentress, 2000; Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014). Apart from this early case, the only other known example of written rules used by mafiosi came in 2007, when powerful Palermo Mafia leader Salvatore Lo Piccolo was arrested in a hideout with a typed list of 10 “commandments” or rules for the organization (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014).

“BBC NEWS | Europe | Mafia’s ‘Ten Commandments’ Found.” BBC, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7086716.stm.

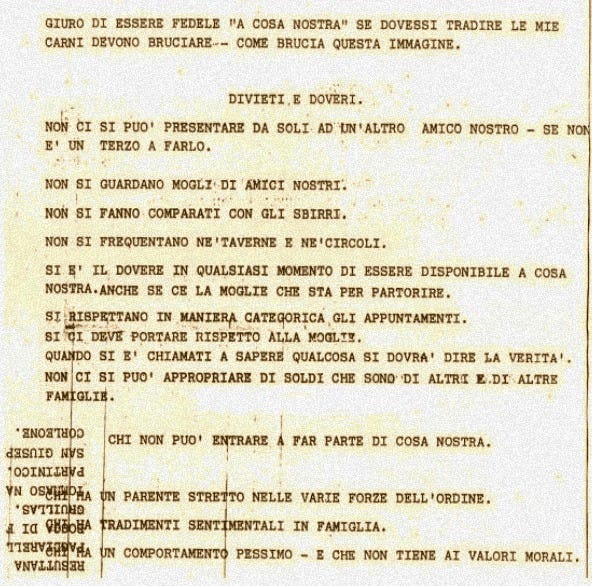

These rare exceptions notwithstanding, the use of written statutes or other formal documents for the organization would seem to have been prohibited by the Sicilian Mafia, with Catania Family member Antonino Calderone describing an “absolute prohibition [that] still holds in the mafia today […] against committing to paper anything that refers to the Cosa Nostra” (Arlacchi & Calderone, 1992). While Calderone did note that the imposition of a regional commission in 1975 to mediate disputes between Mafia Families in Sicily made use of a statute of rules governing the conduct of Families, no equivalent written statute existed for the code of conduct of mafiosi themselves. Calderone asserted that such a thing would not have been necessary even if permitted, as the rules of the Mafia were few and transmitted orally through the socialization of recruits and the initiation ceremony of members (Arlacchi & Calderone, 1992). Thus, the use of written documents relating to the organization stands as one notable way that the traditions of the Mafia and Camorra differed.

Frieno

One of our earliest sources on the Camorra was Swiss-Italian scholar and businessman Marc Monnier, who in 1863 published his book “La Camorra: Notizie Storiche” (Monnier, 1863). Monnier sourced his information on the Camorra from materials gathered by investigations conducted under the direction of Silvio Spaventa, head of public security in Naples immediately following Italian Unification in 1860-1861, as well as interviews that Monnier conducted with camorristi and police officials (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014). Regarding the transmission of Camorra tradition in this early period, Monnier stated, “The sectarians do not know how to read, they have no written laws, (…) their customs and regulations are handed down, modified according to the times, places, the will of the leaders and the decisions of the meetings” (Monnier, 1863).

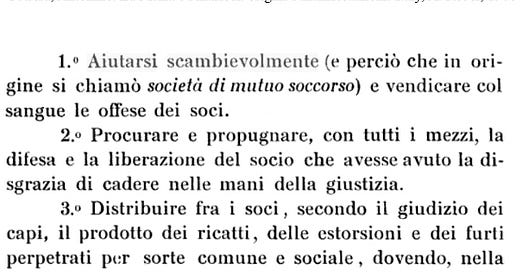

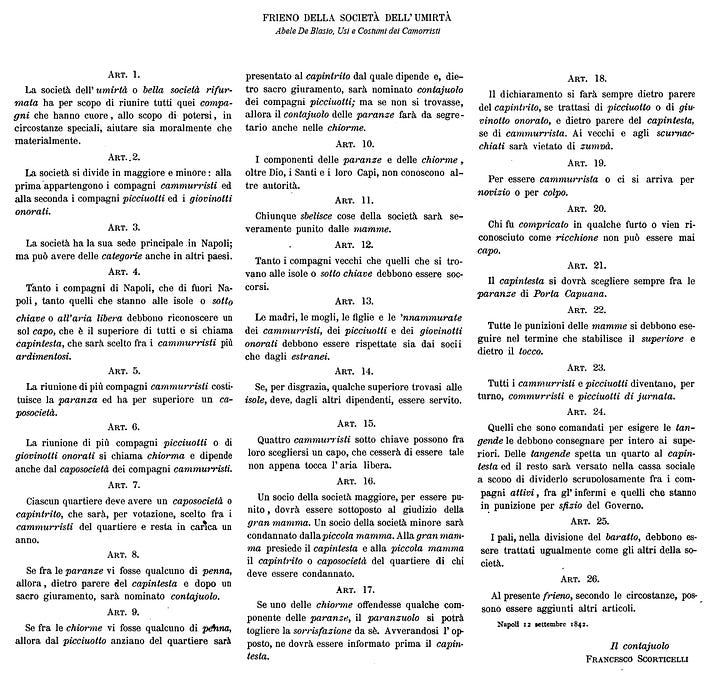

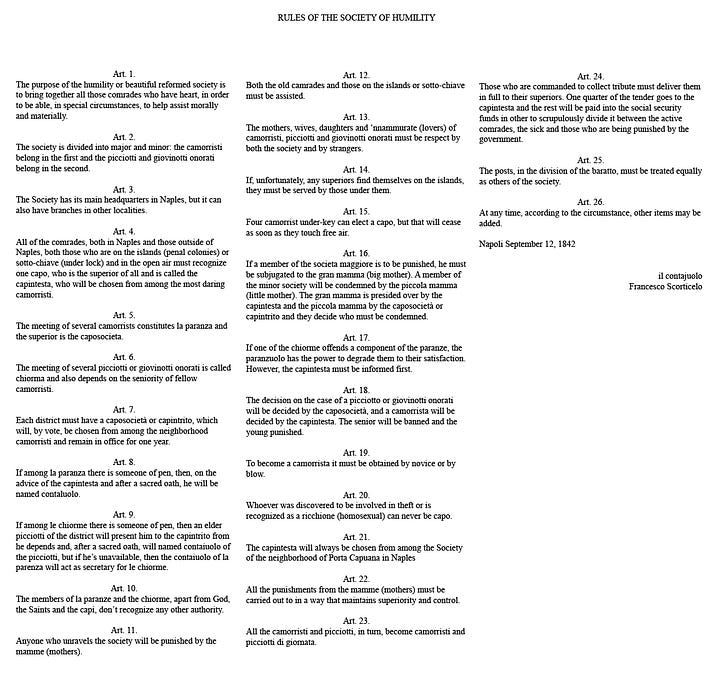

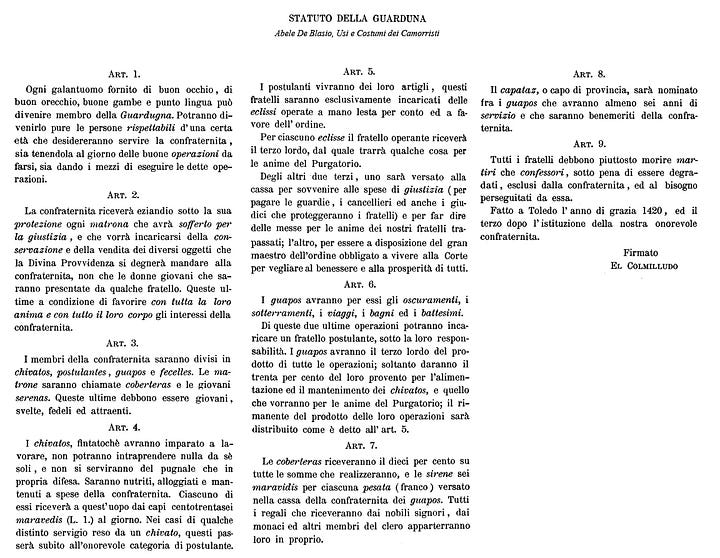

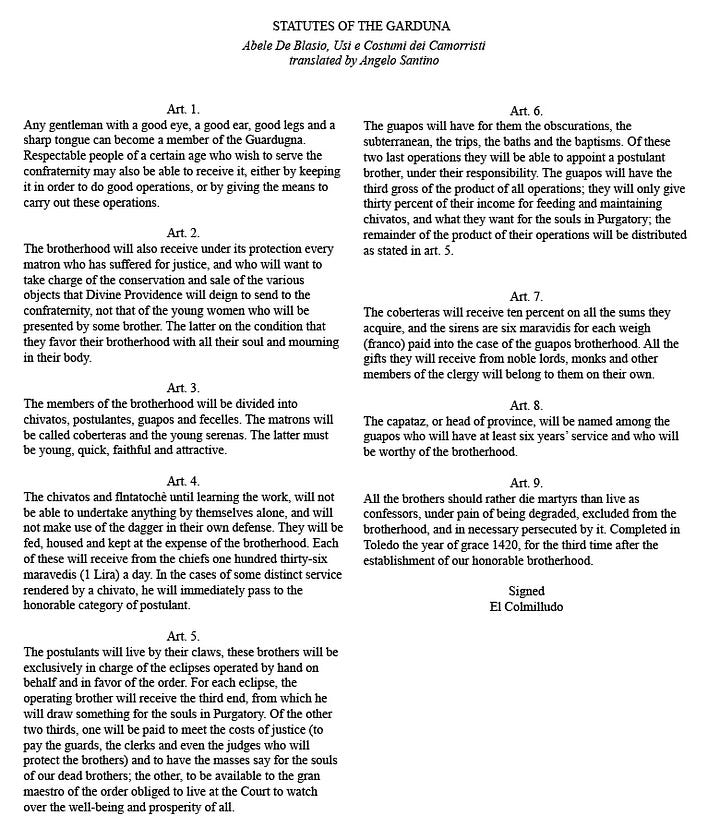

An anonymous Neapolitan author in the late 19th Century published a book purporting to list the “laws” of the Camorra circa 1850, though the author provided no sources or references to support the veracity of the book’s content (Anonymous, Unknown). Somewhat better sourced was Neapolitan anthropologist Abele De Blasio’s 1897 monograph Usi e Costumi dei Camorristi (De Blasio, 1897). In this book, De Blasio reproduced a document titled frieno (freno in Standard Italian, meaning “brake”; the Neapolitan version of the word was presumably used here to refer to the coercive effects of a code of conduct), presented as a written statute of the rules and regulations of the Società dell’Umiltà (“Society of Humility”, a common name for Camorra Societies, along with Onorata Società, “Honored Society”) in Naples. This document was reputedly written over 50 years earlier, in 1842, and attributed to a contajuolo, a Camorra leader serving as a “treasurer” for the Society, named Francesco Scorticelli (De Blasio, 1897). While there is no way to independently verify the authenticity of this document or the manner in which it was produced and recovered, De Blasio presents it as an authentic written statute of the Camorra and goes on to compare this ”frieno” to statutes of the “Garduña, a fictional Spanish secret society (De Blasio was apparently unaware of the Garduña’s literary origins, as Italian scholars since Monnier had erroneously posited that the Garduña had given rise to the Camorra in the past) (Monnier, 1863; De Blasio, 1897; Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014).

(De Blasio, 1897)

One should note that, if this “frieno” were authentic, the document and any others like it seemingly managed to avoid scrutiny for half a century and appear in no earlier accounts of the Camorra. One might even say that is the discovery of such a document was nothing short of a miracle, given that the police archives in Naples were destroyed in an 1857 fire, as the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was nearing its end (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014). Indeed, it is possible that camorristi themselves could have misrepresented the age of this “frieno”, as we have subsequent evidence of Camorra affiliates having misrepresented the age of other documents, presumably to enhance their collective prestige by making their tradition appear older than it in fact was.

An indicator as to its age may lay in Article One of the “frieno”, which refers to the society as bella società rifurmata (“reformed beautiful society”). There is no evidence of just when the Society began to refer to themselves under that name. However, in 1860, Liborio Romano, the Naples chief of Police, essentially deputized members of the Camorra, many of whom became commissioners and policemen. It was around this time when members in Naples tried to present their Society in a new, more illustrious, light (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014).

The rest of the document matches documents discovered decades later, in that it lays out the structure, formalities, rules, and need for secrecy and allegiance in the organization. One aspect that differentiates it from articles found later, however, is the references to the city of Naples. Given its official statement that Naples is the Society’s capital and that it comes from a Neapolitan perspective, one can conclude that this document, if authentic, came from the city of Naples itself. As we will see, other documents found in other areas do not state any capital city or attest to any overarching boss or ruling Society over the Camorra as a whole.

Of course, it is possible that the written articles of the Garduña, first postulated as the origin of the Camorra by Monnier in 1863, served as an inspiration for camorristi themselves, perhaps lending Camorra affiliates the idea of, or format for, such a document (Monnier, 1863; Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014). Indeed, both the Garduña articles and the “frieno” similarly lay out the structure, objectives, formalities, and rules of a secret society.

(De Blasio, 1897)

Along with urban Naples, Camorra Societies were documented in the areas of provincial Campania surrounding the city of Naples, from Salerno and Avellino to the historical province of Terra di Lavoro, since at least the 1850s (Marmo, 2011; Criscione, 2013). In 1858 in Salerno, investigators reported that Raffaele De Rosa, a picciotto di sgarro, kept a booklet containing the rules of the Camorra. Unfortunately, De Rosa fled to the nearby town of Nocera before he could be arrested and the book confiscated (Fiore, 2019). Later reports of the provincial Campanian Camorra made no mention of written statutes or codebooks in the use of affiliates in the Naples hinterland (Marmo, 2011) (Criscione, 2013).

While these accounts suggest that written documents were in use among camorristi in Campania during the 19th Century, the bastion of the Camorra in this era was the prison system of Southern Italy, both before and after the Unification of Italy (Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014). Evidence on the use of written statutes or other documents among the prison camorristi is sparse and conflicting. In the 1870s, a prison Camorra contajuolo known by the alias “Gianbattista Baiocchi” claimed that when he escaped the Nisida penal colony, he took a “portfolio filled with papers of the utmost importance to the Society—list of names, trials, passwords, decrees of death” (Griffiths, 1894). Unfortunately, these documents were never reproduced or described in Baiocchi’s account. Other contemporary accounts of the prison Camorra in this period, such as the memoirs of political prisoners Sigismondo Castromediano or Antonio Nicolò -- who recalled the Camorra that they encountered in the Bourbon era prisons of the 1850s -- or the reports of Silvio Spaventa, make no mention of its affiliates using written documents (Nicolò, 1861; Castromediano, 1895; Marmo, 2011). In 1893, Italian criminologist Augusto Guido Bianchi published “Il Romanzo di un Delinquente Nato”, the autobiography of a prison camorrista from Pargheria in the modern province of Vibo Valentia, Calabria, known as “Antonino M” (Bianchi, 1893). Antonino M recalled his time as a Camorra affiliate in the prisons of Southern Italy during the 1870s and 1880s, providing valuable insight into the dynamics between prison camorristi from various regions of Italy (e.g., Campania, Calabria, Sicily, Puglia, and Abruzzo). Notably, Antonino M makes no reference to the use of written documents by camorristi in his account. Thus, while incarcerated camorristi may have used written statutes to codify and transmit the rules of their organization, verified reports of this seem to have eluded documentation.

1889: The Society of the Mala Vita

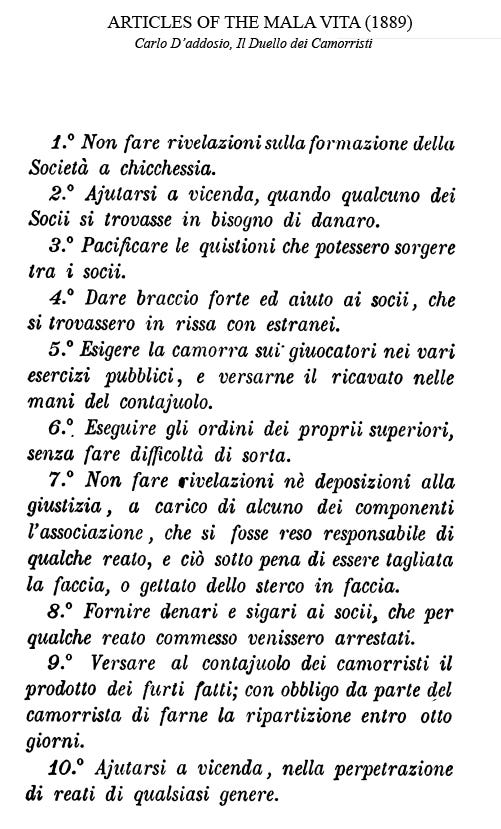

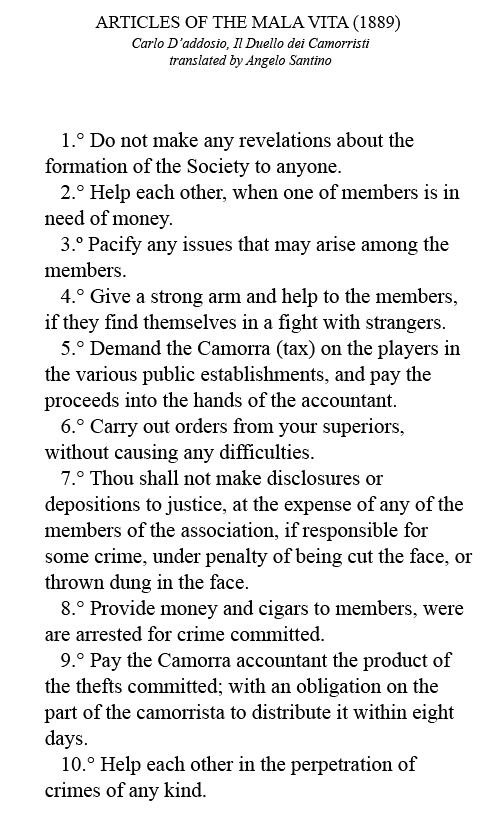

In 1889, a Camorra Society was discovered in the city of Bari in the region of Puglia, called by adherents Società della Mala vita ("Underworld Society”), a name also used by Camorra Societies in Calabria. Also like then-contemporary Camorra Societies in Calabria, the Bari Mala vita began in prison and emerged onto the streets in the early 1880s, deploying the same hierarchical structure as the Camorra in other regions of Italy. In a trial that had 179 accused Mala vita affiliates as defendants in 1891, several affiliates cooperated with the authorities and testified as to the structure, rules, and initiation rituals of the Society.

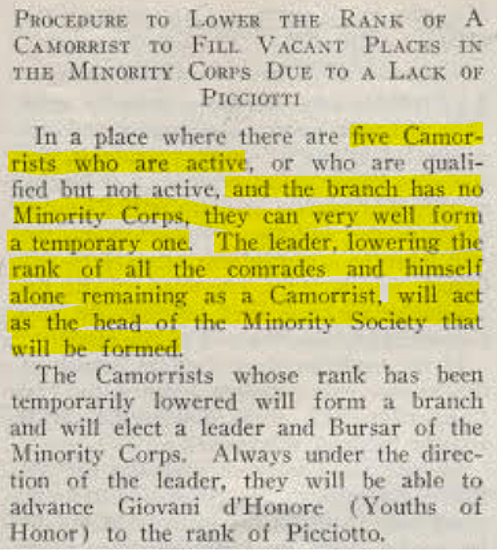

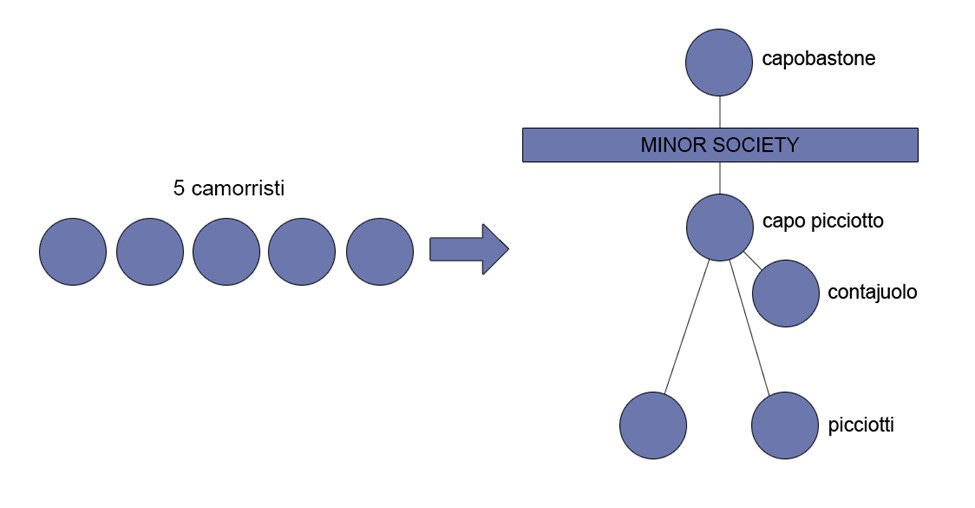

The following description of the Mala vita comes from an 1892 report on the trial by the prosecutor of Bari to the Italian government in Rome: “The Mala vita is composed, or better put, is subdivided, in two branches: one called the Major Society and the other the Minor Society. The camorristi make up the membership of the first, while the second is composed of the picciotti and giovanotti”:

While no mention was made of the use of written statutes or other documents, the rules of the Bari Mala vita, as derived from witness testimony during the course of the 1891 trial, were compiled in the same report:

(D'Addosio, 1893)

While most of these rules specify a code of conduct for the Society’s affiliates, one notable exception is Article 5, which explicitly relates to generating income through criminal means. Rules pertaining to the remission of income generated via criminal activities such as extortion, gambling, and theft have been characteristic of the Camorra, reflected also in the organizational structure of the Camorra, where a leader, the contajuolo/contabile, serves as a “treasurer/accountant” charged with collecting and disbursing the Society’s revenues.

As a well-documented example of a Camorra Society recently transplanted from the prison system, the Bari trial gives us a glimpse into how the rules and regulations of Camorra Societies were passed on orally outside of their origins in the prisons.

Late 19th Century: Calabria

At the time that the Mala vita Society was establishing itself in the city of Bari, Calabrian camorristi from the prisons were likewise establishing Societies in their hometowns following their release. These Societies, which began to use the term ‘ndrangheta to refer to themselves later in the 20th Century, first surfaced in the public record over the course of the 1880s and 1890s, during trials of affiliates in the provinces of Reggio Calabria and Catanzaro. (Dickie 2014).

With one of these trials we get our first documented reference to what Italian researchers call codici (“codebooks”) handwritten or printed books containing the rules and regulations of the Society as well as sets of formulae for ritual initiations and for conducting meetings and tribunals to judge infractions committed by members, ceremonial speech used by affiliates to greet and identify each other, and origin myths of the Society (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010; Malafarina, 1978). An 1888 trial in Nicastro, Catanzaro province, reported the use of a document among local camorristi containing “17 articles concerning the obligations and duties of affiliates, the formula of the initiation ceremony, and the passwords used to recognize fellow affiliates and distinguish them from those of another Society (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010). In 1896, a trial in the court of Palmi, near the city of Gioia Tauro on the Tyrrhenian Coast of the province of Reggio Calabria, noted the recovery by authorities of a codebook in use among Camorra affiliates in the neighboring town of Seminara. The court recorded that this document contained “all the rules, both in relation to the admission of new members -- later referred to by the nickname of picciotto -- as well as the inherent obligations of membership, and to the profit and benefit distributed to affiliates according to their degree of membership” (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010). We can see that as with the rules of the Bari “Mala vita”, this document also detailed the handling of proceeds from criminal activities.

Over the course of the 20th century, a number of similar codebooks were recovered from the persons or homes of Calabrian Camorra/’ndrangheta affiliates in Calabria, North America, and Australia, several of which were discussed and reproduced by Italian journalist Luigi Malafarina in his 1978 book “Il Codice Della Ndrangheta” (Malafarina, 1978). It can be hypothesized that the adoption of written compendia of rules, rituals, and ceremonial procedure was a response to changing social conditions as camorristi initiated in prisons – where the Camorra tradition was deeply implanted and camorristi situated in close, intimate contact with each other – began to establish Societies in communities across Calabria upon their release from prison. The use of written codebooks thus may have served to standardize coded speech and organizational practices across geographically dispersed Societies, reinforcing the ties of solidarity and common identity between local branches of the phenomenon and aiding in the coherent and systematic transmission of a shared tradition to new recruits.

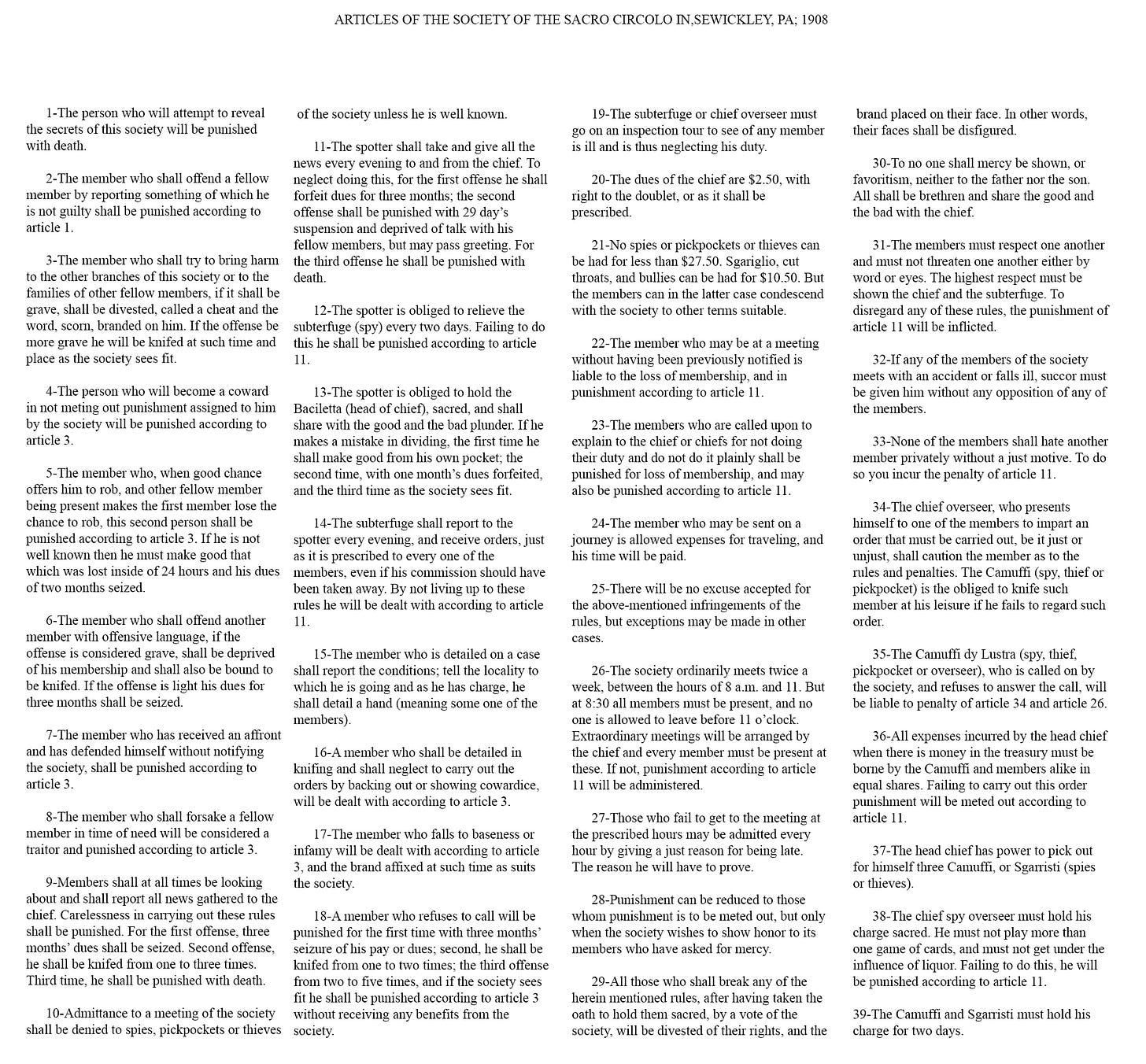

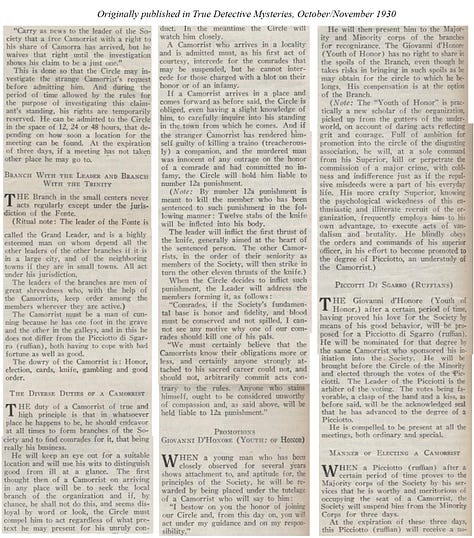

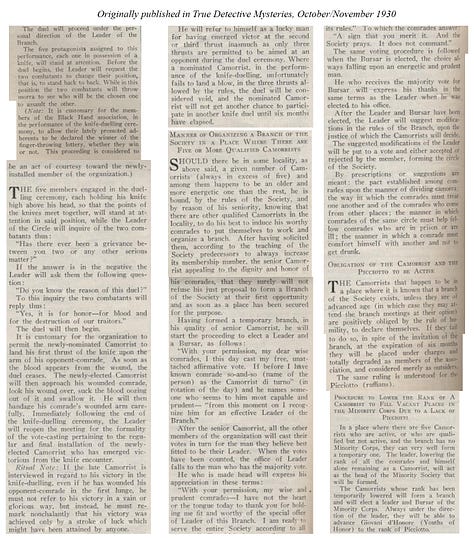

1908: Sewickley Sacro Circolo

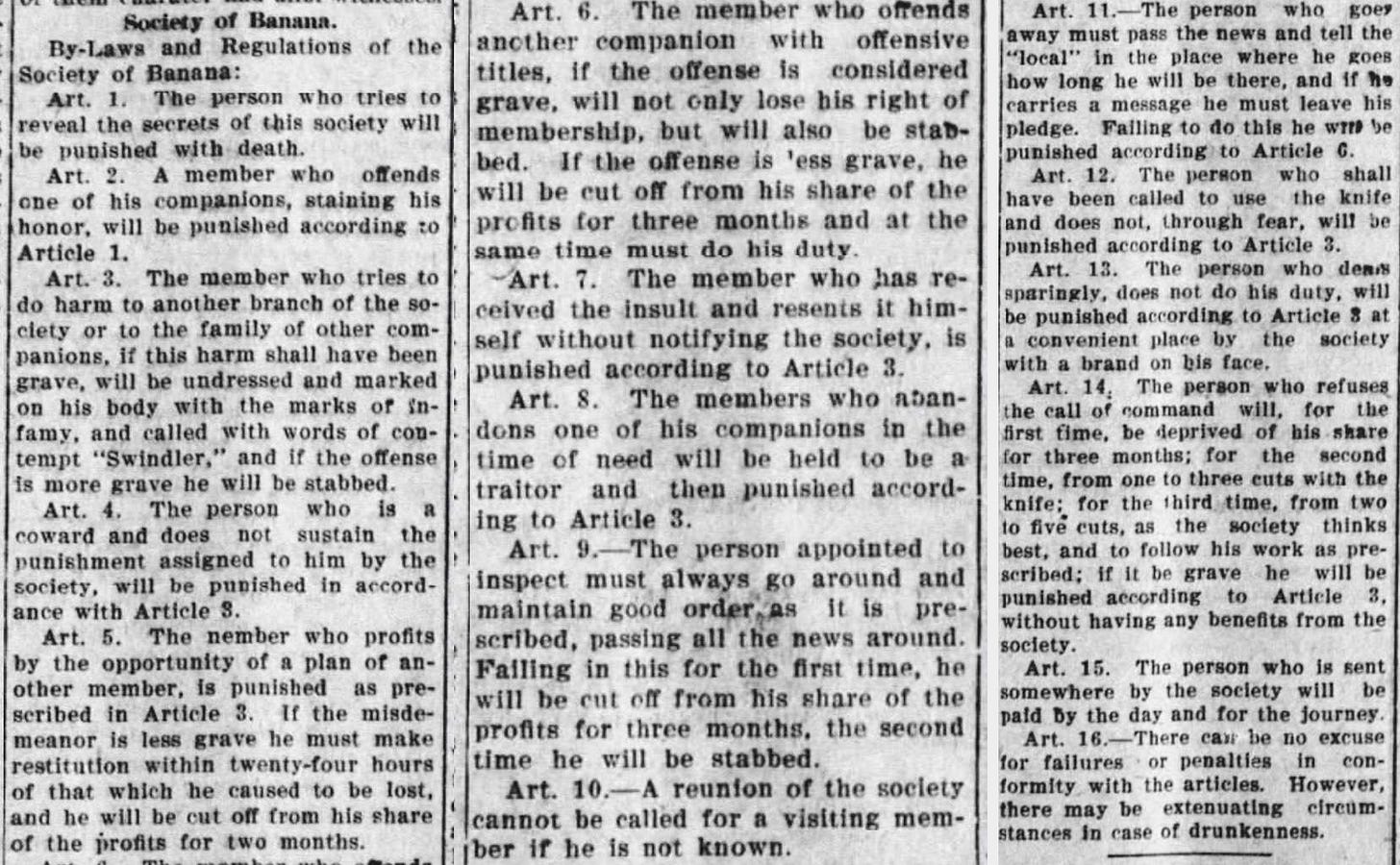

In 1908, letters and other documents were were discovered in a trunk in a home during a police raid targeting alleged members of a “black hand” extortion group in the Pittsburgh suburb of Sewickley, accused of sending threatening letters to extort prominent residents of the area ("Raid Of Black Hand Gang", 1908; Hunt & Barber, Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob, November 2022). The recovered documents referred to the group as sacro circolo (“holy circle”, a name for Camorra Societies recorded also in 20th Century Calabria). Among these documents was a handwritten book described by investigators as containing “19 pages of rules along with another document described as a “catechism” for the installation of the capo, or leader, and letters directed to the “high tribunal” of the Society ("Appeal Sent Sacred Circle Is Evidence", 1908). These documents were translated by Peter Angelo, an Italian detective, with a statute of 22 articles and corresponding punishments printed in The Pittsburgh Press. These articles bear some resemblance to the alleged written “frieno” of Naples and the orally transmitted rules of the Bari “Mala vita”, in that they lay out the conduct, rules, and regulations imposed upon members of the Society:

Though an Antonio Follino in Pittsburgh was alleged to have been an “organizer” of the group, and to have operated a “Black Hand school” for the training of recruits in Pittsburgh where similar documents were found, accused member Raffale Peluso agreed to cooperate with authorities and refused to name anyone else as a member ("Fearful Laws Of Black Hand", 1908; Hunt & Barber, Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob, November 2022; "School For Murder", 1908). While Peluso admitted to being the “head” of the sacro circolo and claimed that the documents in the trunk discovered during the police raid belonged to him, a letter recovered by police stated instead that Tomasso Curcio was, in fact, the “honorable leader of this society” (Hunt & Barber, Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob, November 2022; "Appeal Sent Sacred Circle Is Evidence", 1908; "Gains Freedom for Girl Caught With Black Handers", 1908).

Notably, Peluso hailed from Nicastro, Catanzaro, the same town where a written codebook was first documented in use by Camorra affiliates in 1888, while Curcio and several of the other alleged members were from the neighboring town of Gizzeria ("Trace Black Hand Plot", 1908). We can thus locate the Sewickley sacro circolo within a broader context of Calabrian camorristi making use of written codebooks both in Calabria as well as the rapidly growing Italian diaspora in the US. As with other instances in this period, what were described by law enforcement and the press as “black hand” extortionist groups would appear to be an extension of the highly structured, rule-bound Camorra tradition of Southern Italy.

The 1908 sacro circolo events would not be the last time that the small town of Sewickley would be associated with Calabrian “black hand” activity. In the 1910s and 1920s, the “black hand” in the Sewickley area was alleged to have been under the leadership of Michelangelo Rosato, also a native of Gizzeria (Hunt & Barber, Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob, November 2022). Rosato was closely tied to the Barbaro brothers, natives of Casignana, Reggio Calabria province, who led a Calabrian group in this era in Youngstown, Ohio (Hunt T. B., November 2022; Hunt & Barber, Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob, November 2022). Importantly, this Youngstown Calabrian group, later under the leadership of Paolo Romeo and Domenico Mallamo, inducted members of the Pittsburgh Mafia Family, appears to have remained as an active Calabrian Camorra organization at least through the 1960s, co-existing in the region alongside the Mafia Families of Pittsburgh and Cleveland (Hunt T., Mallamo and Prato: las bosses of Calabrian mob?, November 2022). Again, the 1908 recovery of the codebook of the Sewickley sacro circolo helps us to place this long-enduring Calabrian organization in the greater Ohio River Valley region within a network that drew on traditions stretching back to the earliest documented cases of Camorra affiliates in Calabria.

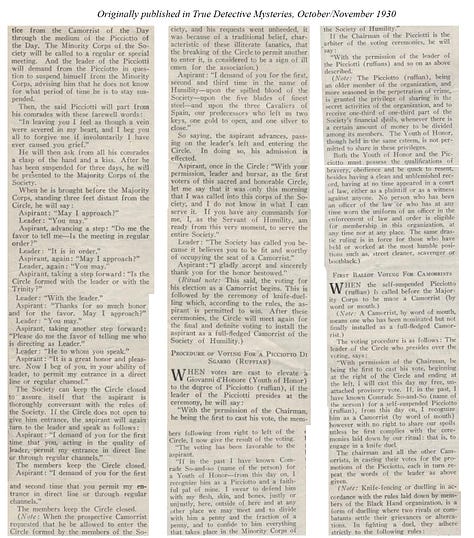

1909: The Banana Society

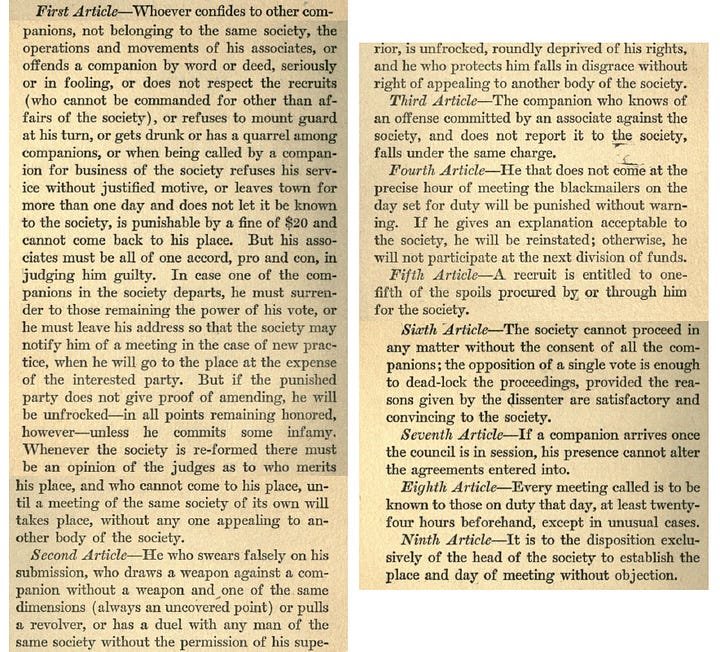

A year later, in 1909, affiliates of another so-called “black hand” group, this time called the “Society of the Banana and Faithful Friends”, were arrested in several towns in Ohio and Pennsylvania and tried on extortion charges. During the course of the investigation, a book containing the “laws and regulations” of the “Banana Society” was discovered in a safe in the Marion, Ohio, home of Salvatore Lima, the Society’s leader, who was born in Trabia, in the Sicilian province of Palermo (Croston, 2022; "Rules of Society of the Banana", 1910). Interestingly, the first nine articles of the “Banana Society’s” rules are identical to those found in the sacro circolo articles discovered in 1908 in Sewickley (minor variations due to separate translations of the original texts to English notwithstanding). As with Sewickley, although investigators reported that a “book” was recovered, only the section of that document detailing the Society’s rules was actually released to the public.

As noted above, apart from some rare exceptions, the use of written statutes has never been recorded as a practice of the Sicilian Mafia. In fact, to do would seem to violate cultural principles of the Mafia tradition, as attested to by the Sicilian Mafia informant Antonino Calderone (Arlacchi & Calderone, 1992). Thus, it may come as a surprise that just such a set of documents were found in the possession of Salvatore Lima, whose family was strongly embedded in the Mafia tradition in both Sicily and the US (Valin, 2018). Given his origin in a familial Mafia lineage in Trabia, a town at the center of a hotbed of Mafia activity in Palermo province, Lima was likely to have been an initiated member of the Mafia prior to his immigration to the United States in 1906 at 28-years-old; following his conviction in the Banana Society case, Lima moved to Oregon and then California, where he became consigliere of the San Francisco Mafia Family in the 1920s (FBI, Memorandum: Subject [Redacted] [2], 1972). His dual nephew and son-in-law, Tony Lima, soon thereafter became boss of the San Francisco Family after transferring his membership from the Pittsburgh Family following his acquittal for a Johnstown, Pennsylvania, murder (FBI, Memorandum: Subject [Redacted] [2], 1972). Tony Lima became a confidential informant with the FBI in the 1960s and 1970s, revealing not only his uncle's position in the early American Mafia but also the history and range of the Lima clan's involvement in what was later termed “Cosa Nostra”, even citing a cousin of Salvatore Lima, Giuseppe Lima, who was first inducted into the Mafia in Trabia before joining the American Mafia (FBI, Memorandum: Subject [Redacted] [1], 1972).

The close correspondence of Lima’s rulebook to that of the 1908 sacra circolo would suggest relationships between the “Banana Society” and the Calabrian Camorra, and there is evidence that similar relationships existed during this period in the US. Mafia member Nicola Gentile later recounted that there were close ties between Pittsburgh Mafia boss Gregorio Conti and Calabrian camorristi in Pittsburgh and Johnstown during the 1910s, while the extortion network of the “Banana Society”, and the familial network of Lima himself, who initially arrived to relatives in Johnstown when he entered the United States, encompassed the Western Pennsylvania region, where both Sicilian Mafiosi and Calabrian camorristi operated organizations in the early 20th Century (Gentile & Chilanti, 1993; Valin, 2018). In fact, Dr. Gaetano Conti, Gregorio Conti’s cousin and fellow leader of the Pittsburgh Mafia, served as a character witness for Meadsville, Pennsylvania, based “Banana Society” defendant Giuseppe Galbo, further indicating that this group was embedded in a network of relationships between Sicilian mafiosi and Calabrian camorristi. ("Rules of Society of the Banana", 1910). We can identify such relationships as foreshadowing ongoing ties that would come to inform the evolution of the American Mafia, as Camorra affiliates of mainland Italian extraction were recruited into the Mafia over the 1910s and 1920s, notably in Western Pennsylvania, leaving a significant legacy of influence on the membership and character of Mafia Families in the US (Organized Crime: 25 Years After Valachi, 1988; Gentile & Chilanti, 1993). Though evidence of a direct relationship is unknown, the Lima clan's presence in Johnstown, as well as Pittsburgh, is significant given the nature of the "Banana Society" documents and the mingling of Sicilian mafiosi and Calabrian camorristi across those specific locations.

While all of the known affiliates of the “Banana Society” were Sicilians from the provinces of Palermo and Messina, early American relationships between mafiosi and camorristi may also point back to the documented participation of Sicilians alongside their mainland counterparts in the prison Camorra of 19th century Italy (Nicolò, 1861; Bianchi, 1893; Castromediano, 1895). Further, outside of the prisons, Camorra Societies were documented in Sicily itself during this period (independent of the Sicilian Mafia), with attestations to the presence of camorristi eastern Sicilian cities such as Messina and Catania, as well as Palermo in the west of the island, in the early 20th Century ("The Maffia: Forty-Four Chiefs Arrested", 1900; Dorsey, 1910; Leopoldo, 1915). The “Banana Society” may thus open a window into sets of relationships between the Mafia and Camorra that otherwise largely went unrecorded.

("Rules of Society of the Banana", 1910; "The Black Hand Rule of Terror is Exposed", 1910)

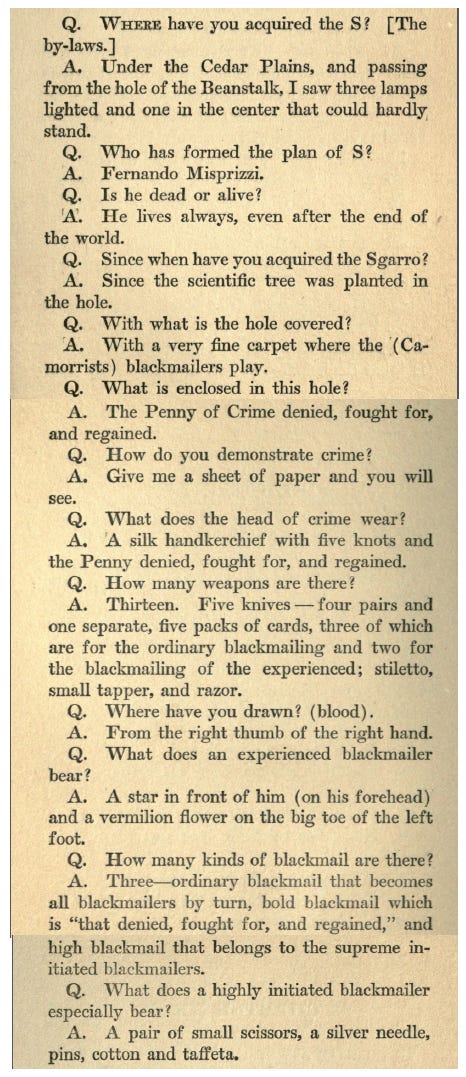

In 1909 counterfeiter Rudolfo Palermo, of Ardore, Reggio Calabria, was arrested by agents of the US Secret Service in Hudson, New York, possessing what was described as an “ominous looking little book” containing the “rules governing the actions of the “Black-Hand Society.”

While this document was not published in full, Secret Service agent and subsequent director of the US Bureau of Investigation William J. Flynn provided some translated excerpts in his book “The Barrel Mystery”, published in 1919 (Flynn W. J., 1919). The rules of the “Black-Hand Society” to which Palermo belonged, fashioned as a formal statute, pertained to the protocol of the Society.

(Flynn W. J., 1919)

The Three Knights

(a) 1890s Favignana

In the 1890s, while working on the penal island of Favignana, physician Emmanuel Mirabella came to learn of a questionnaire between Camorra affiliates to confirm one’s membership in the Society. This coded questionnaire makes references to three knights: one Spanish, one Neapolitan, and one Sicilian, as the founders of the Society.

(Mirabella, 1910)

(b) 1897 Palmi, Reggio Calabria

The Favignana questionnaire’s account of three knights corresponds to a similar version recorded in the testimony of an affiliate of a local Camorra Society during an 1897 trial in Palmi, Reggio Calabria province:

(“The Origins of the 'Ndrangheta of Calabria: Italy’s Most Powerful Mafia (1 March 2011).” [KAJ4] Www.youtube.com, www.youtube.com/watch?v=CR1Gu_7Po38&t=1184s. Accessed 10 Mar. 2024.)

The accounts from Mirabella and the 1897 Palmi witness are the earliest known recorded examples of the fable of “three knights” as the founders of Cmaorra Societies in Naples, Calabria, and Campania. Iterations of this tale, a core element of the self-narrativization of the ‘ndrangheta, would continue to surface in documents from Calabrian camorristi over the 20th Century (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010).

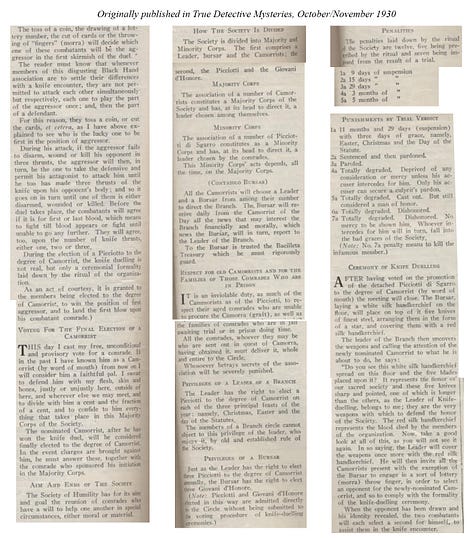

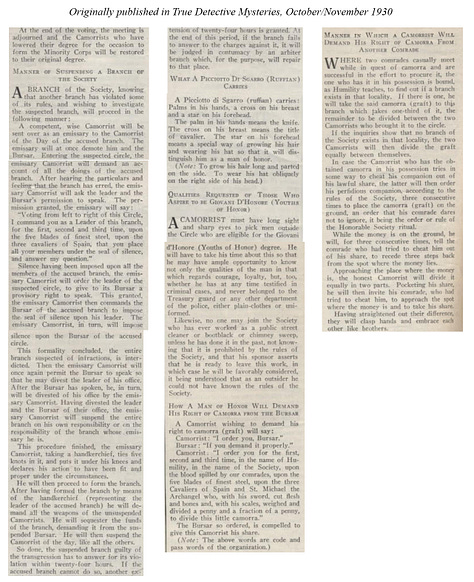

(c) 1928 Olean, New York

Four decades later, in 1928, Giovanni Rotundo, a native of the city of Catanzaro, was the suspect in a shooting attributed to a local “black hand” feud in Olean, New York. While Rotundo had fled Olean with law enforcement on his heels, investigators conducted a search of his room and recovered a printed pamphlet titled I Tre Cavalieri di Spagna (“The three Knights From Spain”) from a trunk.

Rotundo’s book contained a version of the fable of “three knights. Rather than hailing from Spain, Naples, and Sicily, in this iteration of the fable, all three knights are now Spanish, a feature retained in subsequent versions. As in the 1897 Palmi trial, the knights are designated Osso (“bone”), Mastrosso (“master bone”), and Carcagnosso (“heel bone”), though the Olean book notes that these were nicknames in Camorra “jargon”, with their actual names being Gaspare, Melchiorre, and Baldassare. We can note that these are the names of the “Three Kings”, the “magi” from the East who visited the infant Jesus, as celebrated in the Catholic Feast of the Epiphany. The specification of such as the true names of the three knights may have served to further emphasize their Spanish origin, in that popular devotion to the Three Kings is a particularly notable element of the folk Catholic traditions of the former Spanish Empire, which once encompassed Southern Italy (Cardini, 2001).

This document is notable for several reasons. First, it shows the gradual evolution of the Camorra's origin story from the examples documented in the 1890s in Favigana and Palmi. Second, it provides further evidence that the Calabrian phenomenon which came to be known as 'ndrangheta during the 20th Century had its origins in the 19th-century prison Camorra, as previously articulated by authors such as Luigi Malafarina and John Dickie (Malafarina, 1978; Dickie, Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias, 2014).

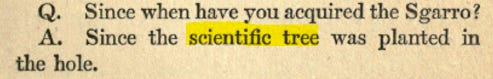

The documents of Rudolfo Palermo in 1909 included a questionnaire that made reference to l’albero della scienza (“the tree of knowledge) (Flynn W. J., 1919):

The book found in Olean again invoked and elaborated upon “the tree of knowledge”, which served to analogize the organizational structure of the Camorra, and remains a central symbolic motif of the Calabrian ‘ndrangheta tradition (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010):

The cover of the Olean book claimed that it was printed in 1790 in Seville, Spain. While this is unlikely to have been factually the case, the assertion of this time and place of publication speaks again to camorristi asserting older origins for their Society than can be objectively documented, as well as a longstanding emphasis on the “Spanish” character of their origins (this mode of self-mythologization can be compared to other secret societies such as the Freemasons, who similarly assert ancient and exotic origins for their fraternal order). The Olean book places the three Spanish knights’ formation of the Society in 1417, while the fictional Garduña society of Spain was said to have been formed in Toledo in 1412, again pointing to the possibility that the unsupported and fanciful theory floated by 19th Century scholars that the Camorra derived from the Garduña may have filtered out to camorristi themselves, informing their own mythology of the origins of their tradition.

Apart from the origin myth, the primary body of text of the Olean book does not focus on the tale of the three Spanish knights but rather serves as a blueprint outlining how the Society is organized -- its rules of conduct, its rituals and formal procedures, as well as punishments for infractions. It is only in Calabria that we see references to the three knights, the symbol of the “tree of knowledge”, and documents that included detailed protocol and mythology of the organization along with statutes of rules.

Arguably, the use of such documents served to provide a method and protocol for how the Calabrian Camorra was able to expand and extend itself to new territories, even internationally, while maintaining relative conformity of tradition between their various branches. As in Calabria in the 1880s-90s, regions of the US in the early 1900s seem to have witnessed what we might call an “infestation” of Camorra activity that aggressively spread and terrorized the wider community. This Olean book helps to shed light on how such rapid spread was accomplished, setting forth a set of prescriptions for the ritually sanctioned establishment and management of new Societies, or ‘ndrine, the fundamental organizational unit of the ‘ndrangheta (equivalent to the “Family” in the Mafia):

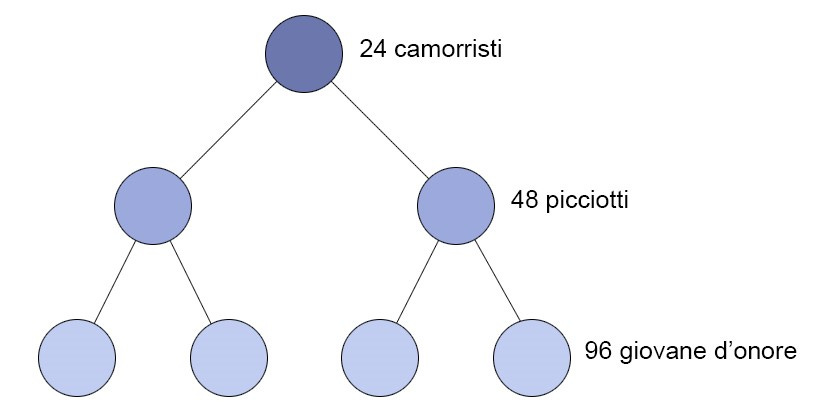

Further, the Olean book lays out the rule that a formal meeting or tribunal of affiliates, called “Corpo di Cavalleria” (“Body of Knights/Cavalry”, also called Corpo di Società, “Body of Society” (Malafarina, 1978; Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010; Gratteri & Nicaso, Storia segreta della 'ndrangheta: una lunga e oscura vicenda di sangue e potere (1860-2018), 2018)), must consist of at least 24 camorristi, 48 picciotti, and 96 giovane d’onore, with each member of the first two ranks, rank having two subordinates beneath him. This bears striking similarities with information that surfaced during the 1911 Cuocolo Trial of the Camorra of the city of Naples, also called Bella Società Riformata, again underscoring that the Calabrian ‘ndrangheta’s and Campanian Camorra stemmed from the same roots in the 19th Century prison Camorra. As in the 1911 trial, the Olean book also prescribed that each camorrista was to be assigned two picciotti. A review of later codebooks recovered in Calabria underscores the frequency that multiples of 12 – as in the prescribed numbers of affiliates for a meeting here – appear in the rituals and ceremonial speech of the ‘ndrangheta (Malafarina, 1978):

(Reveals Practice of Band, 1911)

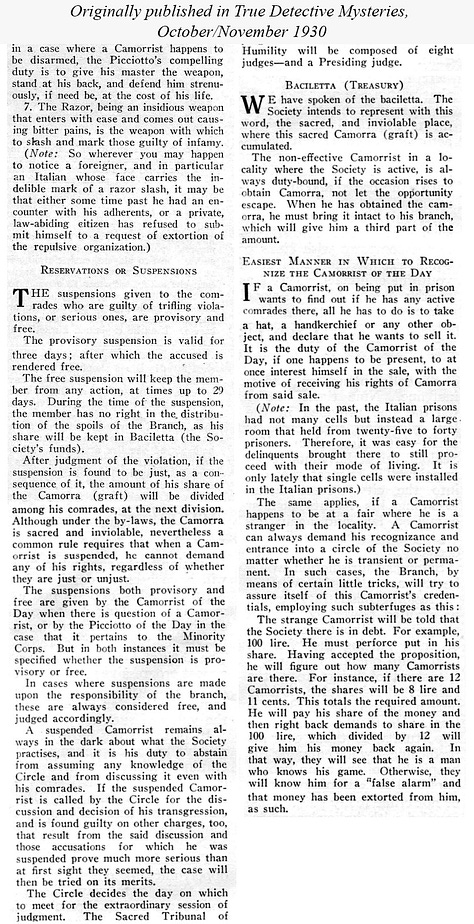

(Ricci, 1930)

It can be readily noted that the 1928 Olean book is an iteration of the same genre of codebooks discovered in the possession of ‘ndrangheta affiliates over the 20th Century. The content of the 1928 Olean book, encoding the rules, ritual speech, and formal procedures of the Society, is similar to a codebook recovered in 1963 from the home of ‘ndrangheta leader Giuseppe Mammoliti in the town of San Giorgio Morgeto, Reggio Calabria, by Italian authorities, as well as a handwritten transcription of the same recovered from the home of ‘ndrangheta affiliate Francesco Caccamo in 1971 in North York, Ontario, Canada. In the below section of the 1971 Caccamo version, translated into English by Canadian authorities, a list of articles details infractions for which members could be punished with a stabbing to the back (Malafarina, 1978). Interestingly, the leaders of the 1909 “Banana Society” in Ohio were reported at trial to have possessed a list of similar rules, the violation of which could result in the same punishment of a stabbing to the back (Croston, 2022).

Several points of the text in the 1971 codebook differ only in details from sections of the Olean book, speaking to the apparent close genealogical relationship of both texts, such as the following segment on forming a “Corpo di Cavallaria” nearly identical to the corresponding section in the Olean book:

The 1971 Caccamo codebook bore the title Come Formare Una Società (“How to Form a Society”), indicating that its purpose was the same as that of the 1928 Olean book: to serve as a set of guidelines for the establishment and management of new branches of the ‘ndrangheta (Dubro, 1985). As with earlier documents in the US, this was again a time of aggressive overseas expansion, with new branches being established in both Canada and the US in the 1960s and 1970s under the aegis of the ‘ndrangheta of the town of Siderno in Reggio Calabria province (Dubro, 1985; Sergi, 2022). We can compare the requirements for establishing an ‘ndrina in the 1971 Caccamo version to the Olean book:

While examination of the 1928 Olean book draws our attention to continuities with a trans-Atlantic ‘ndrangheta tradition, the networks encompassing the “black hand” organization of the Olean area -- as with the “Banana Society” and sacro circolo cases in 1909 -- point also to the history of evolution of the American Mafia. In 1929, investigators believed that a trip to Olean by Stanislao “Charles” Carbone, an alleged “black hand” leader from nearby Johnsonburg, Pennsylvania, was linked to an underworld murder near Dansville, New York (New Clues Pursued In Gang Slaying, 1929). Carbone – a native of the ‘ndrangheta stronghold of Scilla, Reggio Calabria – became closely involved with the Pittsburgh Mafia Family while residing in Pennsylvania and subsequently relocated to California where, like Salvatore Lima, he became a leader in the local Mafia, rising to the position of underboss of the San Jose Family (Valin, 2018; San Jose Family (1962) [Text], 2024). Indeed, Carbone would seem to not have been tiny Olean’s sole link to national Mafia/Camorra networks, as Chicago-based camorrista-turned-Mafia-boss Al Capone was alleged to have visited Olean and fraternized with local figures in the 1920s (Cocca, 2022).

Modern Continuities:

Starting in the 1890s and continuing up until the 2000s in Calabria, there have been numerous occasions where documents “relating to the obligations and duties of members, the oath, the watchword to recognize one another and distinguish themselves from those of other societies” have been attested to or recovered by investigators (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010). The aim of this project is not to retell a complete history of the ‘ndrangheta but rather to emphasize that the incorporation of written documents, intricate rituals, and organizational structures characteristic of the Camorra that emerged in the prisons of Southern Italy in the 19th Century figured prominently in the Calabrian variant of the phenomenon, both in Calabria itself as well as in the North American Calabrian diaspora. The documentation of written statutes and codici in the use of Camorra affiliates in the US provide a glimpse into how this tradition spread in Italian communities in America, beginning only a few decades after their apparent emergence from the prisons and incursion into communities in Calabria itself.

While to outsiders, these Calabrian codebooks -- with their strict codes of conduct and arcane ritual speech -- might seem like an archaic holdover from the past, the ritual speech, and procedures encoded in these documents remain vital elements of the ‘ndrangheta tradition. Vincenzo Macri, Deputy National Anti-Mafia Director stated, "Even today... those rites, those formulas, are viewed as they were a hundred years ago, in the fold of Platì as in the districts of Reggio Calabria, in the back of bar, as in Australian farms, everywhere in short, the 'Ndrangheta expresses the continuity of its presence, of its activity, its proselytizing, and its expansion” (Gratteri & Nicaso, Fratelli di sangue, 2010).

Camorristi, along with importing such documents onto American soil, also imported a criminal subculture that nurtured a dogmatic and cultish devotion to a rulebound Society, one permeated with rituals that served to bind its adherents together in solidarity. When the American Mafia began inducting men from Campania, Bari, and Calabria, they were often bringing in men with a pre-established pedigree in the Camorra. Many of them went on to become leaders of the Mafia in America. And while the use of written documents was left at the door, these members still brought along that same fervent dedication to rules and protocol reflected in the codebooks that we have discussed here.

The authors would like to extend special thanks to Eric Stonefelt, James Barber, Fabien Rossat, Richard Warner, and Lennert van ‘t Riet.

Bibliography

"Appeal Sent Sacred Circle Is Evidence". (1908, 02 09). The Pittsburgh Press.

"Capture Alleged Plotters". (1908, 02 08). Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

"Fearful Laws Of Black Hand". (1908, 02 14). The Pittsburgh Press.

"Gains Freedom for Girl Caught With Black Handers". (1908, 02 09). The Pittsburgh Post.

"Raid Of Black Hand Gang". (1908, 02 10). The Patriot (Harrisburg, PA).

"Rules of Society of the Banana". (1910, 01 26). Marion (OH) Daily Mirror.

"School For Murder". (1908, 02 11). Carlisle (PA) Evening Herald.

"The Black Hand Rule of Terror is Exposed". (1910, 01 26). The Marion Daily Star.

"The Maffia: Forty-Four Chiefs Arrested". (1900, 02 20). The Guardian.

"Trace Black Hand Plot". (1908, 02 08). The Pittsburgh Press.

Anonymous. (Unknown). Natura ed origine della misteriosa setta della Camorra nelle sue diverse sezioni e paranze: Linguaggio convenzionale di essa, usi e leggi. Italy: Tipi di Fil. Serafíní.

Arlacchi, P., & Calderone, A. (1992). Men of Dishonor. Inside the Sicilian Mafia. An Account of Antonio Calderone. New York: William Morrow & Co.

Bianchi, A. G. (1893). l Romanzo Di Un Delinquente Nato; Autobiografia Di Antonino M. Italy.

Calderone, A. (1992). Men of dishonor: inside the Sicilian Mafia: an account of Antonino Calderone. New York: Morrow.

Cardini, F. (2001). Los reyes magos. Ediciones Penìnsula.

Castromediano, S. (1895). Carceri e galere politiche. Lecce: Tip. editrice Salentina.

Cocca, S. L. (2022, 03 30). Jack Dempsey vs. Al Capone: Olean’s 1926 “Little Chicago” Confrontation. Retrieved from Western New York Heritage: https://www.wnyheritage.org/content/jack_dempsey_vs_al_capone_oleans_1926_little_chicago_confrontati/index.html

Criscione, G. (2013). La camorra in Terra di Lavoro: dalla repressione post-unitaria a quella degli anni Venti del Novecento. Napoli: Doctoral Dissertation: Università Degli Studi di Napoli Federico II.

Croston, S. W. (2022). The Society of the Banana in Ohio : A History of the Black Hand. Charleston SC: History Press.

Cutrera, A. (1900). La Mafia e i mafiosi: origini e manifestazioni. Italy: A. Reber.

D'Addosio, C. (1893). Il Duello dei Camorristi. Naples: Luigi Pierro.

De Blasio, A. (1897). Usi e costumi dei camorristi. Luigi Pierro.

Dickie, J. (2014). Blood Brotherhoods: A History of Italy's Three Mafias. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Dickie, J. (2023). The name 'ndrangheta: history versus etymology. Modern Italy, 215-229.

Dorsey, G. A. (1910, 05 26). "Catania Headquarters of the Sicilian Camorra". Chicago Tribune.

Dubro, J. (1985). Mob Rule : Inside the Canadian Mafia. Macmillan of Canada.

FBI, U. S. (1972, 03 10). Memorandum: Subject [Redacted] [1]. FOI/PA# 1219913-0.

FBI, U. S. (1972, 4 13). Memorandum: Subject [Redacted] [2]. FOI/PA# 1219913-0.

Fentress, J. (2000). Rebels & mafiosi: death in a Sicilian landscape. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Fiore, A. (2019). Camorra e polizia nella Napoli borbonica (1840-1860. Italy: FedOA - Federico II University Press.

Flynn, W. J. (1919). The Barrel Mystery. United States: James A. McCann Company.

Flynn, W. J. (1919). The Barrel Mystery. James A. McCann Company.

Gentile, N., & Chilanti, F. (1993). Vita di capomafia. Roma: Crescenzi Allendorf.

Gratteri, N., & Nicaso, A. (2010). Fratelli di sangue. Italy: Mondadori.

Gratteri, N., & Nicaso, A. (2018). Storia segreta della 'ndrangheta : una lunga e oscura vicenda di sangue e potere (1860-2018). Mondadori.

Griffiths, A. (1894). Secrets of the Prison-house. United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall, Id, .

Hunt, T. B. (November 2022). The 1924-25 murders of Dominic and Frank Barber. In Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement (pp. 68-73).

Hunt, T. (November 2022). Mallamo and Prato: las bosses of Calabrian mob? In Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement (pp. 136-148).

Hunt, T., & Barber, J. (November 2022). Barber brothers were allied with Sewickley-Coraopolis mob. In Informer: The History of American Crime and Law Enforcement (pp. 74-82).

Leopoldo, G. (1915, 01 27). "The Terrors of Trailing the Camorra". El Paso Times.

Malafarina, L. (1978). Il codice Della Ndrangheta. Reggio Calabria: Parallelo 38.

Marmo, M. (2011). Il coltello e il mercato : la camorra prima e dopo l'unità d'Italia. Napoli: L'ancora del Mediterraneo.

Mirabella, E. (1910). Mala Vita: gergo camorra e costumi degli affiliati. A. Forni.

Monnier, M. (1863). La Camorra: notizie storiche. Firenze: G. Barbèra.

New Clues Pursued In Gang Slaying. (1929, 09 27). The Buffalo News.

Nicolò, A. (1861). Narrative of ten years' imprisonment in the dungeons of Naples. Italy: A. W. Bennett.

Organized Crime: 25 Years After Valachi. (1988, April 11, 15, 21, 22, 29). : Hearings Before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs. One-Hundredth Congress, Second Session.

Reveals Practice of Band. (1911, April 17). The Pittsburgh Post. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: The Pittsburgh Post.

Ricci, D. A. (1930). Black Hand Exposed At Last. True Detective Mysteries.

San Jose Family (1962) [Text]. (2024, 02 21). Retrieved from LCNBios: https://lcnbios.blogspot.com/2024/02/san-jose-family-1962-text.html

Sergi, A. (2022). Chasing the Mafia: 'ndrangheta Memories and Journeys. Bristol University Press.

Valin, E. (2018). "Former San Francisco boss supplied info to federal agents". Retrieved from The American Mafia: https://mafiahistory.us/rattrap/sanfranlima.html

[i] We use the terms “Calabrian Camorra” and “’ndrangheta” interchangeably here in reference to the same historical phenomenon, which emerged in the late 19th Century in Calabria. While trials in the late 19th and early 20th Century in Calabria referred to this organization, variably, as Onorata Società (“Honored Society”), Società dell’Umiltà (“Society of Humility), Società di Camorra (“Camorra Society”), Picciotteria (“Organization of Picciotti”), or Famiglia/Circolo Montalbano (“Montalbano Family or Montalbano Circle”), beginning in the 1920s the term ‘ndrangheta, derived from the local Calabrian Grekaniko variant of Greek, was recoded as a synonym for local Camorra Societies. In the decades following World War 2, ‘ndrangheta became the predominant usage by both adherents and outsiders (Dickie, The name 'ndrangheta: history versus etymology, 2023).

[ii] Following World War 2, some mafiosi in the United States began using the terms Cosa Nostra (“our thing”) to refer to their organization, while their Sicilian counterparts subsequently followed suit. Prior to this, adherents of the Sicilian mafia, both in Sicily and America, typically used terms such as Fratellenza (“Brotherhood”), Fratuzzi (“Dear Brothers”), or – like the Camorra – Onorata Società (“Honored Society”) to refer to their organization. Here, we use “Mafia” to both the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and its American offshoot.