The American Mafia- La Cosa Nostra- was imported from Sicily. Each and every LCN Family that existed or continues to exist was founded by immigrant Mafiosi who imported and reestablished the exact same model from Sicily into America. This has been confirmed by former Mafiosi with a flair for history, federal investigators and through historical research.

But as history has defaulted into fable, Mafia mythology has reinforced the narrative that the American version was created by Lucky Luciano in 1931. In Peter Maas’ Underboss, he summarized it by stating that “In 1931, warring factions of the Italian underworld, primarily Neapolitan and Sicilian gangsters, came together to form Cosa Nostra.”

Joseph Valachi, America’s first public informant who, in 1963, testified at the McClellan Hearings laying out his 30-year long association with the New York Mafia. While his story details many different aspects of Mafia culture, one reflected his vantage point as a Neapolitan outsider inside a Sicilian brotherhood. While most of his Italian American contemporaries were joining the New York Mafia, he encountered another fellow Neapolitan, while serving time in Sing, one Allesandro Vollero. who advised against his joining the Mafia, cautioning:

“If there is one thing that we who are from Naples must always remember, it is that if you hang out with a Sicilian for twenty years and you have trouble with another Sicilian, the Sicilian that you hung out with all that time will turn on you. In other words, you can never trust them. (Maas 1968)”

Indeed Joseph Bonnano, Sicilian-born boss of the New York family for more than 35 years that still bears his name today, admitted as much in his own 1983 autobiography, A Man of Honor, where he wrote:

Men of my Tradition were always loath to associate with non-Sicilians. The reason for this was not bigotry but common sense. They knew that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to pass on a tradition unless one is exposed to it almost from the cradle. (…) A tradition is not something that one learns overnight. It is the work of a lifetime.

Even southern Italians, from the Naples region or from Calabria, who otherwise have much in common with Sicilians, cannot fully appreciate the old Traditions of Sicily.

For example, southern Italy has in the past given rise to such groups as the Camorra and the Black Hand. These non-Sicilian groups were orders formed to accommodate the interests of thugs, highwaymen and extortionists. It is a grave mistake to identify these groups as being the same as the “Families” of my Sicilian Tradition. Americans, we well as southern Italians, have often made this mistake. Camorra and the Black Hand never existed in Sicily. They have nothing to do with what Americans refer to as “the Mafia.

Because of the melting-pot effect in America and the need for recruits during the Castellammarese War, we Sicilians found ourselves accepting into our confidence many non-Sicilians. Men joined our ranks who didn’t fully appreciate the tradition, or only understood it in a very rudimentary and superficial way (Joseph Bonanno 1983).

Joseph Valachi, like many gangsters of his generation, was an American rendition, having grown up in East Harlem around a mix of Italians, Irish and Jews. His interactions with other Italian criminals had little to do up front with their regional origin and more with money-making ventures and general associations. However, within the Mafia its very true as the saying goes: birds of a feather flock together. Following the Castellammare War, Valachi would transfer to the Neopolitan-centric Genovese Family and placed into a decina headed by Antonio Strollo aka Tony Bender. And while Valachi’s eventual mob nemesis would be another Neapolitan member, Vito Genovese, Valachi claims to have never forgotten the wisdom that Allesandro Vollero confided to him.

Born in April of 1885 or 1889 in Gragnano, outside of Naples, Allesandro Vollero emigrated to America at some unknown point to reside in South Brooklyn where he ran the infamous Navy Street Café along with Leopoldo Lauritano, who along with Pellegrino Morano of Coney Island would all be convicted as members of the Camorra for the murder of Nick Terranova, a rival in the Sicilian-American Mafia. Vollero would eventually meet Valachi in Sing where he became a mentor, his parting advice to Valachi was:

“Talk to me just before you get out of here (prison), and I will send you to a Neapolitan. His name is Capone. He’s from Brooklyn, but he’s in Chicago now” (Maas 1968).

While the name of Allesandro Vollero is less recognized, Al Capone is a name that needs no introduction. Aside from being credited, falsely, as the founder of the modern Chicago Outfit, his name has come to represent the American Mafia in its bloody glory years, largely looming more as legend and myth than as an actual individual.

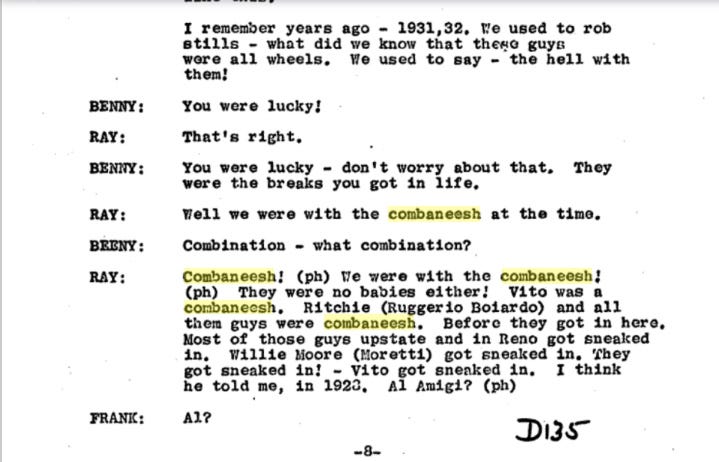

In the 1960’s two Genovese Family members were picked up discussing history and the subject of Al Capone came up:

Frank: “Al?”

Fred: “Al was a neighborhood chamise (ph).

The reference was part of a larger discussion:

Ray: “Well, we were all with the combaneesh at the time.”

Benny: “Combination - what Combination?”

Ray: “Combaneesh! (ph) We were with the Combaneesh. (ph). They were no babies either! Vito was a Combaneesh. Ritchie (Ruggerio Boiardo) and all the guys were Combaneesh. Before they got in here. Most of those guys upstate and in Reno got sneaked in. Willie Moore (Moretti) got sneaked in. They got sneaked in! – Vito got sneaked in. I think he told me, in 1923.”

The FBI didn’t realize what was being discussed at the time, they couldn’t even decipher the word being said. However, all of the names being mentioned shared one thing in common: they were all early non-Sicilian members of the American Mafia. But what was the accurate phonetic word they were trying to convey when they wrote “combaneesh?”

Camorristi or the singular Camorrista (anglicized to Camorrist and pronounced “Gaw-more-eesh” was in reference to affiliates of the Camorra. “We were with the Camorristi” or “Al was a Brooklyn Camorrist.” Rumors of Al Capone’s involvement with the Neapolitan-derived society are nothing new, allegations have been made, skepticism has been raised, but the smoking gun rests on the fact that the Chicago organization he headed before joining the Mafia later had its origins in the Camorra. Its first identified boss in Chicago was James Colosimo who would be linked in 1910 to Francesco Filasto, New York’s Camorra Capobastone (“Headstick”) or boss and his nephew Antonio Sacca who would later relocate to Chicago.

The Camorra remains obscure to most Americans and western crime watchers simply because it hasn’t had a significant presence in the USA since the 1920’s and left very little traces of itself behind. There have been rumors and various tidbits of its existence but these leads, when explored seem to lead to nowhere definitive. In 1988, the US Senate, in their Investigation Inquiry into organized crime included a timeline, which for the date of September 7, 1928 reads:

Antonio Lombardo, boss of the Chicago Family, was shot and killed on a downtown sidewalk. The importance of Lombardo’s death is that it is said to have sealed the merge of the LCN and the Camorra in the Chicago area. Reportedly, Al Capone, head of the Chicago branch of the Camorra, was offered membership and a ranking position in the LCN if he would have Lombardo murdered (Affairs 1988).

The evidence will show that the Camorra, like the Mafia, was exported from Italy by immigrants, not only the city of Naples or the Campania region, but also from Cosenza, Catanzaro and Reggio in the Calabria region of Italy. Contemporary sources label the early Calabrian society currently known as ‘Ndrangheta as the Picciotteria due to court transcripts but it very much was the exact same society as what was called the Camorra in Naples, from the structure to the blueprint to the mutual recognition, these were all local branches of a larger organization, each with their own localized idiosyncrasies.

Today’s ‘Ndrangheta can be described as an evolution of the Camorra that existed in Reggio Calabria from 1850-1920. There is no shortage of records that describe the Camorra’s system and structure from Naples, those records coincide with Camorra groups in Calabria and also Calabrian Camorra groups in America. Records from 1850’s Naples can be juxtaposed alongside records from Catanzaro in the 1870’s, Reggio Calabria in the 1900’s, Westchester, NY and Pittsburgh, PA in the 1910’s, Oleans, NY in the 1920’s, Youngstown in the 1960’s to Toronto in the 1990’s. The links are there for anyone who was looking.

The evidence for this is confirmed on the Italian side in the book, Il Romanzo Di Un Delinquente Nato. Published in 1893, it is the semi-autobiographical story of one “Antonino M,” a prisoner originally from Porghelia in the province of Catanzararo, he detailed his life as what he called a Camorrista within the Bourbon prison system. Within his memoirs, he revealed that the Camorra in prison was divided by regional factions- Provincial (Neapolitan), Abruzzesi, Calabresi and even Sicilian- but unified as part of a larger system or entity, they shared mutual recognition of each other as members and when members were transferred to different prisons they carried their membership with them. The Camorra’s membership, reach and affiliations extended far beyond the city of Naples, Campania into Bari, Cosenza and Reggio Calabria. What has been labeled the Picciotteria was just a euphemism for something much larger.

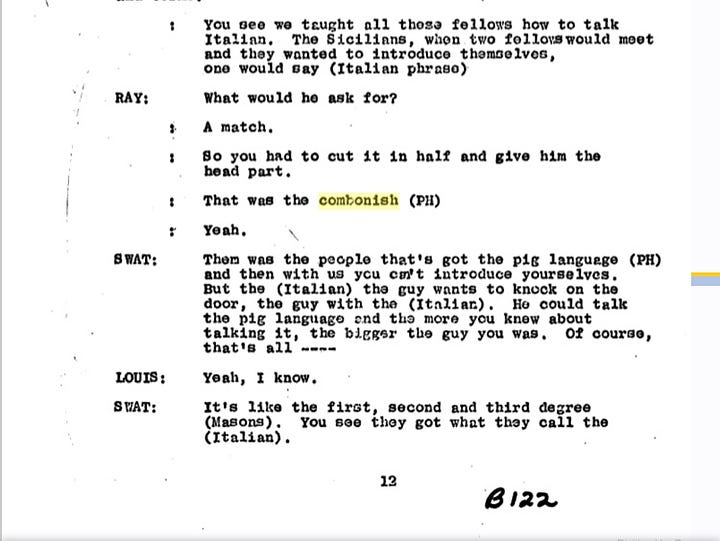

This is also exemplified on the American side in the 1965 Steve Magaddino wiretaps:

Steve Magaddino: “And I – I always saw to it that there was room in our house for a few “picciotti.” This also helped to win the respect for “ours” because the “picciotti” with the “Camorristi” –

Bill: “These are the Calabrese! Not Sicilians.”

Unknown Man: “Yeah!”

Steve Magaddino: “Calabrese. At first I used to carry on a fight against those people. Those Calabrese – I used to fight them. Then, a time came that I did not get involved anymore.”

Never once did Steve Magaddino refer to this Calabrese group as Picciotteria or ‘Ndrangheta, nor did Rocco Racco of Hillsville nor Salvatore Marra of Westchester in the 1910’s. They used the term Camorra. So the history of what became known as the ‘Ndrangheta originates with the Camorra, any history that doesn’t make this connection is an incomplete history.

So before we delve into the American Camorra, we need to learn its roots and for that we will have the go back to 19th century Italy with a focus on Southern Italy before we can begin the cover the American side. And with that, the more popular Sicilian Mafia will also be discussed and compared to, because people tend to view the Camorra through a Mafia-centric lens and the Mafia-itself as an organization continues to be not fully understood. There were similarities but also striking distinctions, indeed both groups exhibited very different criminal cultures very early on. Their descendants in early 20th century America, men like Genovese, Boiardo and DeCarlo descended from a criminal subculture that Mafia aristocrats like Joseph Bonanno described disdainfully. This mainland criminal subculture will also be examined because while the Camorra declined in the US in the 1920’s, elements of its culture and traits can be seen in the Families of the Genoveses, Chicago, New England, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and San Jose, all of which had a high percentage of non-Sicilian mainland members.

The modern American La Cosa Nostra or LCN has been exhaustively traced and connected to the Sicilian Mafia, it has rightfully been concluded to be an extension of the same Society and not an American copy-copycat. To members like Joe Bonanno or even Michael DiLeonardo in recent decades, they understood their affiliation to be to the Mafia regardless of whether they used that term as a title. But the mainland-elements of the American LCN also have their own history, alongside but separate from the Sicilian experience.

In a recent episode of The Mob Archaeologists, hosted by Richard Warner, Eric Stonefelt, Chicago Tony and yours truly, we interviewed Michael DiLeonardo and I asked him about Bensonhurst (primarily Sicilian) and downtown Brooklyn (primarily Campanian) and he recalled the cultural differences between the two neighborhoods reflected during his time growing up in the 50’s-70’s, he responded that Sicilian Bensonhurst viewed the downtown Italians as “Camorrists” which he used to describe them as “more rough, less refined.” He wasn’t using the term to describe an organization but instead was making the distinction between Sicilian and Southern Italian culture. It should be noted that when asked by me previously, he confirmed that he never heard the term ‘Ndrangheta used. His own experience largely coincides with what one informant from Milwaukee provided in 1964:

MI T-1: “The Mafia (…) generally looked down upon the Camorrista as ruffians who lacked principles.”

The story of the American Mafia has been told from the Sicilian-angle, my intention is to tell it from opposite end, the mainland-centric subculture of the Sicilian-subculture which influenced men like Frank Costello, Nicodemo Scarfo and John Gotti later. These men, at least the two latter, were never formally affiliated with anything but the Mafia, but their non-Sicilian origins were relevant to them. In the 1950’s, Costello was politicking for New England to install what he specified as a “Neapolitan” as boss; Philip Leonetti recalls Scarfo’s classification of Sicilians as businessmen and Calabrians as gangsters; when Gotti was elected boss, he purposely ruled out selecting men like Joseph Corrao for an administration position for being “too Sicilian” despite Corrao being a 4th generation American.

While the American Mafia remains an outgrowth of its Sicilian counterpart, it remains distinct from it due to its large mainland element, men like Al Capone and John Gotti who came from a different subculture who, as Bonanno concluded, “cannot fully appreciate the old Traditions of Sicily.” Which is true, they didn’t appreciate the “Traditions of Sicily” because men of Campania and Calabria had their own traditions. And ironically, while these mainlanders may not have appreciated the Sicilian tradition, they were quite rigorous in following and adhering to it, sometimes even more so than their Sicilian counterparts.

Just what are the traditions of Sicily and how do they compare and contrast with the traditions of the mainland? The answer is twofold, traditions can refer to regional cultures including criminal subcultures, but Tradition with a capital T that Bonanno was referring to, was that of the Mafia as a Society. Both need to be evaluated with each other because both made their way into America and influenced the men who came after them and the qualities they brought into the American organization.

The argument over what constitutes a true mafioso has been a matter of conjecture for the past century. Generally, Sicilian-descended members opted for a conservative approach, more white collar and were prone to nepotism within their society. In contrast, Italians and even Sicilians who lacked those bloodlines were often blue collar, more overtly criminal. Los Angeles informant Jimmy Fratianno, a non-Sicilian of Molise descent, established himself in the underworld as a killer and from his point of view, was the measuring tool for what constitutes a true mafioso. He criticized the sons of members, believing they inherited their positions and discounting them as deadheads. Decades later in another city, Nicodemo Scarfo, a non-Sicilian of Calabrian descent contrasted himself with his former Sicilian boss, “Bruno was a racketeer, I’m a gangster.”

Indeed it might have been Salvatore Gravano, a Sicilian from a non-Mafia bloodline, who moved between both factions who characterized the middle ground best: “A gangster can be a racketeer but a racketeer can never be a gangster.” Obviously he would have more in common with the ‘street guys’ of Gotti and DiCicco’s ilk than he would the Mafia aristocracy of Paul Castellano and others, whose family can be traced back to the Palermitan Mafia.

So the ongoing disagreement over what constitutes a mafioso largely depends on the individual’s background. Members of Sicilian origin with a long-family connection tend to be more conservative in style, trying to cloak themselves in legitimacy. Whereas, members from non-affiliated background lacking the historical link, may be less infatuated traditions and annoyed by traditional mafioso culture, opting to publicly enjoy and show off the proceeds of being a criminal. Otherwise what’s the point?

These conflicting points of view are rooted in the criminal subcultures of Southern Italy and Sicily. The quintessential Mafioso and quintessential Camorrista came from different backgrounds, had different characteristics and took different approaches when it came to criminality.

John Dickie, one of the subject’s leading experts on Italian Mafias, past and present, said just as much in his book, Mafia Republic: “The soberly dressed Sicilian mafioso has traditionally had a much lower public profile than the camorrista. Mafiosi are so used to infiltrating the state and the ruling elite that they prefer to blend into the background rather than strike poses of defiance against the authorities. The authorities, after all, were often on their side. Camorristi, by contrast, often played to an audience.”